The United States was founded on principles crafted by minds marinated in an excellent classical and theoretical education. Today, students at our undergraduate institutions obtain a bachelor’s degree without having read a single book start to finish on their own, and even the young need remedial math and English. There was a time when pupils were expected to have almost intermediate skill in the classics—so what went wrong?

The issue is rooted not only in policy but also in how our generations have taken on parenting and their overall approach, from ensuring we raise intellectually curious individuals to being indifferent to the matter. Arguably, the most socialist belief I have is the idea that education should be the most funded element of our government. However, with a seemingly backward correlation, we have been pouring billions of dollars into our federal education department. What we have failed to realize is that this is, in fact, a causation.

So, what do we do about this? Abolish the Department of Education? Create a more rigorous curriculum reminiscent of a preparatory school accessible to the working class? The answer addresses an issue that has plagued policy for decades in this country, and it’s one we ought to fix fast, before we see our children going even more backward than they already have.

When we look at issues that serve as systemic as this, we need to look at pivotal points within our education system. Speaking for the absolute, our compulsory standards in education have gone up tenfold since colonial times. What I looked at here that was wrong were the overall standards being neglectful for the needs of a service-based economy, but that segues into an issue that’s far too complex for me to address.

What we really want to look at is the history of higher education and the means by which we would need to enter it over time. From the time of Harvard College’s establishment in 1636 to the foreseeable future, a bachelor’s degree used to be drastically different from what they corroborated to their versatility. A bachelor’s degree at one time wasn’t meant to serve as a qualification but more so a statement.

Translating Homer’s Odyssey to Latin, reciting long passages from it in Greek, and being able to thoroughly examine a text by Hegel were not by any means what an attorney past or present would need to do to navigate their job, but educated men could do that, so that’s practically what it was. And when I say men, I mean men, because women wouldn’t end up making an entrance into higher education until the middle of the nineteenth century, nor would they be let into these initial institutions like Harvard until the middle of the twentieth.

Marginalized groups were gatekept with minimal exemption, and when something of the sort would happen, they would also be well-connected like their white peers, but still able to access it before any woman would. So needless to say, this system was very backwards and needed some change, and it did in fact come.

Now, what I meant by the foreseeable future would be roughly two and a half centuries, until World War II. Now, along with needing to be well-connected and white, you also needed to be wealthy, as these schools would charge the same crazy rates in contrast to the average salary, except with student loans being nonexistent, you would need it in cash. A year at Dartmouth College would run you around 70% of the average worker’s salary in 1920.

Today, costs have skyrocketed to over 100% of the average worker’s salary, which is for reasons I will soon explain. But in a time when you could make a good enough living to purchase a two-story house and support a family of five with a job that didn’t even expect a high school diploma, nobody really wanted to complete an undergraduate degree.

And on top of that obvious economic barrier, you would also need to go to a preparatory school that would prepare you for the institution’s specific entrance exam, since the SAT also wasn’t a metric used to standardize the education pupils from all walks of life would get. Which you would need connections and money to get admitted to one of those to begin with, so college was seen as not only a luxury good but one that also served as an asset for cultural capital.

Now, with all of those negative aspects being spoken about education’s accessibility, allow me to give some good news before this pivotal point. We began establishing state-funded institutions in the nineteenth century to train for more practical things such as engineering, mathematics, agriculture, teaching, and many more things.

This opened a door of mobility for the working class to obtain higher education, as these places would also charge relatively nothing. The UC system, for instance, charged a flat fee, and after that you would have no further responsibility to finance your education aside from room and board. Again, while there was no clear incentive to obtain an undergraduate degree, the opportunities to do so were increasing steadfastly.

Now, enter into the Second World War, and we’re met with a profound sense of gratitude for our servicemen, who looked evil in the eye and defeated it swiftly and with an uncharacteristic display of bravery. Our politicians even knew these guys needed far more than a parade to understand our deep-seated gratitude for their service.

This is when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the G.I. Bill, most notably, and a variety of other subsidies. And when I tell you that this was huge, that is a gigantic understatement. We would both provide financial compensation to purchase whatever their hearts desired and finance their college education. Now the number of men who wanted to obtain a higher education skyrocketed, as they needed a means to support the families they were now creating.

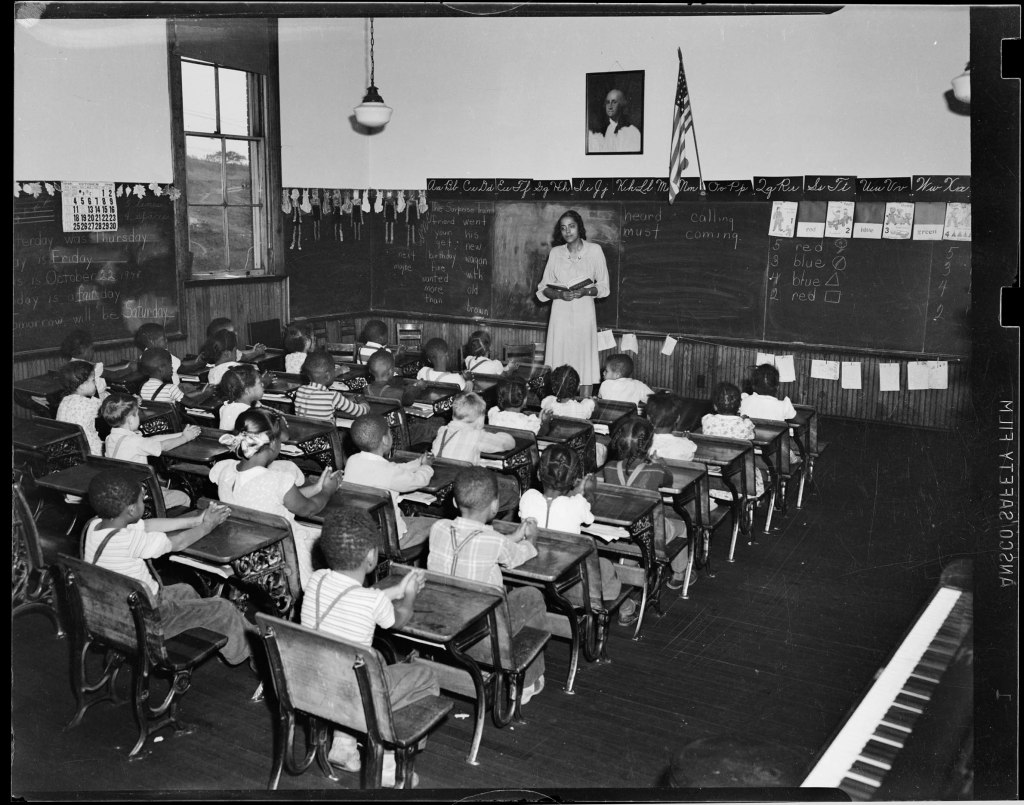

This played a huge role in the accessibility of higher education, not only for the working class but also for African Americans. Despite all of the absurd tropes that existed about them being weaker than the white soldiers, they now had an opportunity to provide not only themselves but their children with social mobility through this opportunity. Though in the Jim Crow South, they would have little options for higher education, this allowed many of the great thinkers in the civil rights movement to obtain one. In a way, this not only helped the advancement of our general population but the civil rights of our marginalized population, so it was in fact a huge deal that would help the progression of every American society by an astronomical amount.

Now, when we go back and look at all of this, it’s an incredibly positive event for our population. But let’s look at this from the perspective of these undergraduate admissions offices. In the decades that preceded, we would typically have applicant pools ranging from the dozens to the hundreds, where about 80% of them would comprise the first-year class. Now fast forward to the 1945–46 cycle: they suddenly began to get thousands of applicants coming from a plethora of backgrounds.

The question now is, how do we compare a kid that went to a one-room schoolhouse in Wichita, Kansas, to someone that went to Phillips Andover? These grading scales and the material they were learning are now distinctly different. This is where the SAT began to be utilized as a standardized metric that admissions offices could use. And despite the criticisms I and many others have with standardized testing, alas, we can ensure that both individuals alike have a shot at earning a spot in the first-year class at Harvard College.

After this major breakthrough, we saw an explosion in college enrollment for the better part of almost four decades after the war. With the variety of students seeking a more well-rounded education, the idea of the major and making the classics and philosophy more of an optional thing happened, which was necessary to appeal to the many pupils these schools began to receive.

When the baby boomers would eventually begin attending these institutions in the 1960s, these universities began to get the tendency to operate as a business, since now undergraduate education gradually began to turn into a checklist as opposed to an optional credential meant to state intellectual rigor. With this mindset change, these institutions gradually placed a higher emphasis on retention over mastery and entertained having more amenities whilst leveraging the alumni and network to bolster the brand name to make the institution more desirable.

Now college had become a universal means to an end as opposed to a supplemental means to an end, and now we have the children of the boomers who began to treat it as a consumer good that would be obtained through tutors to get a higher score on the SAT, admissions coaches to get guidance on how to make a stellar application. However, the only difference between the consumerist aspect in the early twentieth century to the 1980s was now it was more so about obtaining the credential to receive these exceptional opportunities and means that the previous graduates of these institutions enjoyed.

However, the reason why these individuals enjoyed the star-studded life that these children pursued was not because they had a bachelor’s degree from an elite school but because of the intellectual rigor they had provided. So with this, the value of an undergraduate degree decreased very steadfastly, to the point that it became the new high school diploma, which now was a universal standard across every walk of life, now that everyone from everywhere could go to high school.

When we talk about the second biggest reason as to why our collegiate system is the way it is today, it’s mostly due to the idea that the system lost its meaning, making the pupils feel indifferent. Along with feeling they need to check this part of the list, they are now becoming burdened with debt. What happened to these flat fees that the state schools charged, you may ask? Wasn’t there a time Berkeley cost virtually nothing? Yes, but the boomers transitioned it in an extremely negative way.

The United States saw entrance into the Vietnam War in the 1960s, and now we see these places of intellectual rigor become places of activism, which in turn became very violent. From the shooting at Kent State to the students burning ROTC buildings down and fighting police officers on the street in Berkeley. This caused Ronald Reagan to cut the education budget in California during his governorship. This amount was substantial enough to hurt the UC schools. Now they needed a way to subsidize this revenue they lost, which in turn helped them make education affordable.

This is where the public schools began to charge comparable rates to the elite private schools, which were also becoming places of activism as opposed to rigor. While many people here blame Reagan for the existence of student loans and outrageous tuition rates, which would only skyrocket due to the demand for bachelor’s degrees, I blame the boomers for turning these once-intellectual platforms into activist corals, which should have absolutely no place in higher education.

And fast forward to today, where we are also dealing with similar educational cuts that simply are going to worsen the cost of these bachelor’s degrees. While I understand the reasoning for these cuts, like the Reagan era, it’s a great deal of hypocrisy, as the very generation of people running our government caused students to believe that this is suitable conduct on the college campus.

This isn’t a critique of the cause—whether it was keeping our young men out of a war that didn’t benefit us by a long shot or trying to stop Israel from flattening the Gaza Strip—as I agree with both, but the basis that the brand of activism promoted by college students doesn’t incentivize intellectual rigor but encourages passion and outspoken nature, which is arguably bad for civil discourse.

Activism isn’t a mutually exclusive trait from intellectual rigor, as we can see through Martin Luther King Jr., who went to institutions in a time where they emphasized intellectual rigor needed for him to be an effective activist. While there was emotion in his cause, the means in which he achieved the cause were anything but. College should teach you the intellectual means MLK had to become a great activist, not be a place of it.

With all of this being said and done, we have students in my generation heading to undergraduate institutions that shouldn’t be there. The fact that these institutions also created a more business-oriented model doesn’t help and is creating courses of study that aren’t even necessary to get a bachelor’s degree in and are more trade-based than anything.

While we do need to turn these places into intellectually rigorous environments again, the means that we must use to obtain such a goal aren’t as simple as cutting educational funding, because in turn, all it does is make education less accessible. We need to ramp up our career education exponentially and create a more transparent model between these institutions and the youth, because the truth is, almost half of the time certain majors shouldn’t even exist and in turn give people the false illusion that a trade being misrepresented as a college degree is something to go into an unfathomable amount of debt for, which is anything but true.

When we strive to fix issues like this, it isn’t a means of a single executive order but a collection of legislature that will actually require a lot of work. But if we can rid society of the stigma that college is a means to an end regardless of what you want your end to be, we will be more on track on seeing to it that all of us simply shouldn’t go to college, and that’s okay.

Sources:

Harvard students are graduating ‘without finishing a book’

It’s Time for Harvard Students To Pick Up a Book | Opinion | The Harvard Crimson

Reagan’s Legacy: A Nation at Risk, Boost for Choice

January 17, 1967 Statement of Governor Ronald Reagan on Tuition | Ronald Reagan

Free College Tuition: What Really Happened When We Tried It | TIME

How the G.I. Bill Changed the Face of Higher Education in America | TIME

Leave a comment